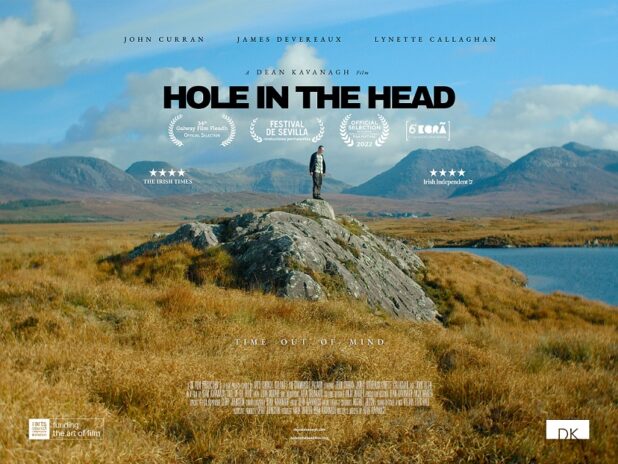

Hole In The Head – Interview with Director Dean Kavanagh – In this article, Craig interviews up and coming Irish Director, Dean Kavanagh. A fascinating insight into the filming process.

Irish film-maker Dean Kavanagh recently released his sixth feature film Hole in the Head to critical acclaim. The Greystones based film-maker has directed seventy shorts and six features; his work having been described as experimental, and an important new direction for Irish film. It’s not very often I feel the need to take notes watching a film, but as I dived deeper into Kavanagh’s filmography, immersed in the quiet explosions of image and sound, I ended up with pages of notes, and quite a number of questions, which the director was kind enough to sit down and speak with me about recently. During this interview, we talked about his approach to film and the importance of the cinematic space, his love for retrograde technology, and the experience of making his latest feature.

Craig: Thank You for meeting me Dean. Your latest film Hole In The Head is described as a Dark Comedy Drama about memory and trauma, underpinned by techniques you have been developing for the past fifteen years. Can you tell me about the journey you’ve been on and how Hole In The Head came about?

Dean: When I finished my previous film, Animal Kingdom, in 2017 it was like closing a book on purely improvised cinema. Going forward, I wanted to do something a little bit different, so I started writing again. I wrote short stories with the intention of adapting them in the future and Hole in the head was one of them. When it came to developing something a few years later I thought “well that one’s an interesting story as it deals with personal filmmaking”.

I have been working a lot with retrograde, moving image technologies. I’ve always appreciated different formats; making films on Hi-8 tape, VHS and VHS-C tape and editing on VCRs when I was a child. I began to miss that tactility, and so I wanted to bring that into what I was doing digitally, somehow. A lot of the skills come from being very curious with that technology growing up. And that curiosity continued after those machines and processes became superannuated.

So it kind of developed from that, and in my work the technology is really part of the drama itself. For example in Hole in the Head the story information is not only told through character dialogue because the image and sound want in on the action; they’re part of the narrative and they’re characters too.

Craig: Would it be fair to say that Hole in The Head was something of a departure for you in that it’s little bit more narrative driven than your previous work?

Dean: Yeah it was a decidedly ambitious step in that direction. The idea of using story in a much more open way was announcing itself more and more in my work. My films have always inhabited the grey zone between experimental film and narrative; they are a hybrid form.

In terms of your work, there are characters who seem to emerge and re-occur from film to film, as well as certain images and themes; for instance, you’ve described the idea of memory as a kind of virus. Is that something you’ve been interested in exploring?

Dean: It’s something that’s interlinked with cinema as a whole; the idea of remembering, and cinema being a mechanism for that but also a physical carrier; a format for preservation. I am interested in the disintegration of these carriers and of memory itself, as well as ideas surrounding imperfection and how technologies that we’ve created are also fallible in capturing ‘truth’.

I do like that regularly quoted Orson Welles line that “a film is never good unless the camera is an eye in the head of a poet.” Memory institutions are like organs also, and they require archivists to preserve and programmers to curate; the onus is on them to articulate the truth- archivists are like detectives- but imagine a detective trying to preserve a crime scene for decades?

Nothing is perfect and everything has the capacity for total failure. When it comes to memory as a theme, I suppose I enjoy the idea of an unreliable narrator; a space where the systems of memory fall apart and from that you can have a very interesting set of circumstances to have a story.

Craig: And of course in Hole In The Head, the protagonist John Kline is trying to recreate scenes from his past, engaging with all of this technology to try to make some kind of sense of his life. Was that a strange experience for you to delve into?

Dean: I enjoyed fabricating his family tree and then bringing it to life through faux archival material. I was in a tricky situation of imagining myself as this character and how he might feel about this history, and then of course the possibility that he has completely fabricated this history and what type of person would do that in real life, what kind of mind is at work there; what is his goal? These are all of the things that I am doing within the context of filmmaking itself. So I can answer some of those questions. In this case, there lies the permeable membrane between creator and character.

I wrote backstories for all of the characters but for John I wrote two and I decided that it would be more interesting for me to deny resolving his mystery, though I do lean fairly heavily in one direction. Once the character was prepared, I enjoyed creating ‘worst case scenarios’ for him and just dropping him into it like Mr. Bean onto the cobbles. Mr. Bean is a profoundly melancholic creation actually. There’s no real parallel between both characters, other than the idea that they sort of materialise out of nowhere. I drew influence from films like The Shout, Theorem and Visitor Q. When it comes to John Kline, we are never laughing at him, but rather at the scenario he finds himself in. John Curran had a great impact on the creation of this character; I ran a lot by him. Those who know John also know he is a comic mastermind.

I asked Dean about his previous film Polar Nights, and his experience working with archival material. In Polar Nights we see footage that is over a hundred years old interspersed with images of still skies, the efforts of explorers trying to haul their equipment across the polar landscape is juxtaposed with characters sitting in a room as time passes. I was interested in finding out how this archival footage interacted with his film-making.

Dean: I’m fascinated by archival material, for example you mentioned Polar Nights; in that film I incorporated footage from Ernest Shackleton’s expeditions and so on. Polar Nights was made with a zero budget. When I completed my 2014 feature, Return of Suspicion, which was a six month project, I had used up all of my favours and I needed to lie low for a while. When you have no money your talents become the currency, and you enter into a transactional existence. Even after the six months of completing a feature I wanted to immediately create another one, but this time a traditional adventure film! So Polar Nights emerges as the antithesis of what a standard adventure movie should be, and it was made by me in a room, on my own, over three months.

I had developed a process for recapturing or re-photographing material and so I processed all of this archival material as my own footage. I also re-processed my own film materials in the same way; stuff like rushes, deleted scenes and other elements from the ‘kill your darlings’ bins from previous projects. The idea was to make the archival material ‘my own’ and to divorce myself from the footage I had originally shot over the years. In this way it all becomes ‘found footage’.

Craig: It must be a strange experience putting together a film in that way!

Yeah, the title comes from a particularly nasty bout of insomnia I was experiencing around that time. Once the film was finished, I watched it right the way through, as you do. What I did next was a bit odd, I deleted it all. The film was good, I was happy with it but I suppose I felt as if I had watched it too many times while editing and I wanted to make it afresh. I have a hard time thinking back on this because it was months of work. What I should have done was taken a break and had a test screening. I just deleted it and then recut it entirely in 48 hours because I wanted to surprise myself. I never watched the full, final cut until the premiere in Cork. That was exciting! It’s nice to be surprised.

Craig: Speaking of archival material and your own footage over the years, I think you’ve mentioned this idea of giving it a “second death” where you know some of this old footage has a chance to be seen in a different context. I wanted to ask you about that. You’ve said that film making can be like a kind of a séance, and so I’m wondering what the role of the director is in that?

Dean: That line comes from the Book of Revelations, it’s a reference to a great lake of fire that unrepentant sinners are tossed into. How awful! That’s the second death. While I’m not religious, I’ve always been enamoured by that phrase and with found footage, one is up-rooting the material from its origins and intention, and killing it a second time, throwing it into that lake of fire. Death imagery has been part of the cinema lexicon since the beginning, with Maxim Gorky commenting on his first experience of moving images as “a train of shadows” or “motion’s soundless spectre” and Jean Cocteau’s description of cinema as “death at work”.

When we film ourselves we become a little undead, forever bound media carrier where our images are doomed to decay on the rotting film strip or as corrupted data on a flash card, but there are always traces even in data loss. When we turn these images into found footage, we give them a new life and a new death. I like that sentiment and, in many ways, Hole in the Head is a film closing in on these ideas. I see cinema as a kind of séance.

Craig: Many of your films are created with a zero budget; can you tell me a about how you got started in making films and where this philosophy emerged from?

Dean: Within the industry, I did just about every job you can think of from coffees to development, pre-production, production to post, exhibition, marketing and preservation. I did all of this because I wanted to become self-sufficient. I’m constantly trying to gain new skills. For example, in order to run my own data management I took courses in computer programming, and to shoot in a projection booth I trained as a projectionist. I’m not suggesting a film director needs to know all these things but if you’re working with low budgets then it can only help. Either way, it improves your knowledge so that when you eventually hire an expert, you can speak some of their language and maximise time. Killian FitzGerald did a phenomenal job as sound designer and mixer for Hole in the Head, I could never have done that myself. I was able to get the very specific sound I wanted because I could communicate to him about specific techniques and processes. I knew some of these things because I investigated audio standards and read Dolby manuals. I actually mixed my previous feature myself and in the most Bobby Bowfinger fashion imaginable: by sneaking in and out of cinemas across the East Coast with 100s of DCP files, a pen, and a notepad. Not even Herzog would have you doing that! That was a painful three and a half months. Working with Killian, on the other hand, was a fun and exciting two or so weeks! I learned so much from him.

My first paying job in the industry was doing pink pages at Ardmore Studios. I started making films much younger though, at around 10, and later I went to film school. I always hear people kicking against film schools- I never understood that. As someone who came from a low income family, the very notion of touching an Arri master prime lens before I was fifty years old seemed impossible. Film school put real equipment in front of me, and that was very exciting. Then I graduated into recession Ireland, which wasn’t very exciting. And people were under the opinion that artists should work for free, which wasn’t very exciting either. In earnest, I wanted to direct but I didn’t really want to do music videos and things like that because I felt the director-for-hire thing could be a compromise for an artist. Look at me now! I’d shoot your wedding if the price was right! Nothing wrong with that, the great Czech auteur Jan Nemec was a wedding videographer. If you’ve seen my films, then you know that I’m the last person you’d want doing your wedding. But I’ll do it.

Craig: And how has did that process unfold during the pandemic. I know Hole in the Head was made during a strange time. Was it difficult working under those conditions?

Dean: The pandemic was tough across the board. You couldn’t go out to get milk and a head of lettuce without a disaster management plan.

My producer Anja Mahler and I made a rigorous COVID safety plan for Hole in the Head . Moving people and equipment into the country and then around many different counties was tricky. It was a tough time to produce anything and in terms of insurance, I was more or less told by companies that it would be preferable for me if someone were to be hit by flying shrapnel rather than catch covid on the set! Thankfully, neither happened. Covid was a legal black hole.

It was a bit easier for indie productions to navigate the pandemic because of scale. I suppose, working in a DIY way for so many years meant it was easier for us to solve the problems that the pandemic threw at us. I spent so many years working without a safety net or a commercial infrastructure, so when you stripped back the complexities of the government restrictions and analysed the production implications, it was nothing new.

Craig: I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the cinema itself. When the doors to cinemas were shut people in some ways turned to other means of watching films. I wonder if there are some who will not go back. You have an on demand section on your website where people can watch your films online, how does that affect the cinematic experience?

Dean: While my films are designed with a cinema theatre in mind, the most important thing for me is that people can watch them. So streaming them as H264 or a ProRes download in stereo is not the end of the world, but we should not take the in-person cinema experience for granted.

When I first decided that I would make ‘experimental films’, I was about eighteen and I was just putting stuff up on Vimeo. It was difficult to get a lot of experimental films into festivals, specifically because I wasn’t following a purely structuralist or formalist approach to experimental cinema, or a purely research driven approach to art in general; I’m not stapling a Beckett quote to a cabbage. I am interested in craft and technique, as much as I am fixated on narrative and materiality. The internet was a way of sharing my work with people without the bureaucracy or gatekeeping that festivals impose. Also I didn’t really want to play the festival ‘game’, I simply wanted to find likeminded people and share my work, I was looking for a community.

If you are not represented by a distributor then you spend just as much time networking and racketeering as you do making the film. At that time, I didn’t participate in that process because I thought it would cheapen the intimacy of the films somehow. I was probably right. I had been submitting to festivals since I was in my early teens so I knew the process. But when I reached 18 or 19 I felt I needed to protect my films, in a quasi- political way, from all of that whoring; I didn’t think they could survive it; they were very delicate and personal objects. It can be difficult to programme films like mine because they can disrupt the playlist. These films required a dedicated programme strand but I rarely found one. At that time, a lot of those streaming websites and forums were finding their feet, and the internet seemed like an ideal space to find an audience.

As we chatted, Dean relayed to me the striking memory of his first time in the cinema and how this had a huge impression on him.

Dean: I think my first cinema experience was going to see The Empire Strikes Back on its re-release run when I was in junior scouts, and we were brought to the Savoy. It was such a massive space, over 1000 seats. The film had already started and the hall was packed. There was none of this fancy biased lighting, it was an usher and a flashlight urging you to your row of seats, I remember being quite frightened as it was so loud and dark. I was never a Star Wars fan, I appreciate the craft but they never moved me. As a child I remember being bored and looking around the room; it was like an ocean of faces all lit by the screen in these flickers and pulses. I remember looking up, it must have been like skyscraper high; there was a window with this huge cone of light and smoke and dust. The room was more interesting than what was on the screen. I remember thinking, wouldn’t it be great to make a film that activates the space like that, and how extreme can you go…

Craig: What are some ways you’ve tried to preserve this cinematic effect?

Dean: With the advent of digital we have lost our portion of darkness. A film projector releases the celluloid in front of a bulb, and before the lens we have a mechanical shutter that breaks the stream of images with an intermittent frequency of darkness, enabling our brain to process the images in a realistic flow of movement. The digital projector has no mechanical shutter because the digital image sequence does not require one. On a material and formal level I’ve used a lot of techniques to reintroduce certain frequencies of darkness. On a narrative level, I am interested in perception and what might take place in that darkness; in the frequencies the brain edits out.

Craig: I suppose that brings us back to the character John Kline, since that’s what he’s doing in a way. He’s learning and understanding this language of cinema. In having almost put your own process to screen in certain places, seeing artists playing with light and doing experiments and developing techniques, there’s a lot of documentation of that.

Dean: Yes, exactly. While I had seen countless comedy or mockumentary films about clumsy or bungling filmmakers, I had never seen one about an experimental filmmaker. You know, the kind of ‘serious artist’ type? I thought about James Benning, a filmmaker I greatly admire, whose work involves shooting incredibly long unbroken takes of the natural and man-made world. I can’t think of a more serious artist. What if he had a camera jam early on and stood there for 10 minutes thinking it was turning over perfectly. That’s quite a sadistic scene to create, so, what if the character is already aware that there is no film in the camera and yet he still stands there, recording nothing for 20 or 30 minutes? There’s something disturbing and profoundly amusing about that, to me at least. So I like to mix these surreal moments in with the genuine malfunctions. Naturally, most of these things happened to me. I don’t view myself with any stoicism at all, I’m just a part-time masochist, and it was easy to create the circumstances for John’s character out of those experiences. I have a fondness for John’s character though, he isn’t trying to brainwash or soapbox and spout aphorisms, he’s just making his films and his true motivations are unknown, maybe even to himself.

Craig: That’s one thing I noticed watching your work, it’s often like characters are almost looking into a mirror or when you stare into a mirror for a certain point of time, like some of us used to do as kids where you stare at a mirror and get kind of creeped out or whatever but that, is that something that you’re consciously developing; that relationship between the viewer and the film itself as though they’re peering into each other in a way?

I think of cinema as voyeurism, both in the activity of creating movies and in the act of watching them. In my favourite films I see the story undress; unburdening itself from expectation or a specific template or, in some special cases, from what we expect a film to be. It can be a private dance between the filmmaker, and if that is conveyed it can engage the audience, even in the quietest moments.

Craig: Well, thank you for chatting with us today Dean, thanks for coming. Can you tell people about where to see your films? I know you’ve got your own on demand section on your site where you can access your films on Vimeo.

Dean: It was a pleasure, Craig. You can find information on me and my films at https://www.deankavanagh.com/